As we moved along Norbert points out some of the beautiful flowers we pass, explaining that a common misconception amongst people is that the indigenous species are ‘messy’ or ‘ugly’, this was certainly not what I was seeing in front of me, flowers varied in size, quantity and colour, and the sweet scents invading my nostrils was certainly a pleasant welcome. ‘But not all exotics are invasive or bad’ I comment, now playing devil’s advocate. From my time managing Colobus Conservation, we would often see the colobus gorging on flamboyant flowers, bougainvillea and mango leaves and so I had always seen these as the lesser evils of the exotics. Norbert agreed but was quick to point out that actually there was a native flamboyant to the coast, but again people go for what they know, most likely unaware of the alternative, the flowers were smaller, but just as beautiful.

Next, we approach a collection of several Ficus species, again all found along the coast. I was thrilled to see so many, assuming that there were only one or two found here. I was also on a mission to gather research on species that attract wildlife, and from my brief knowledge of fig trees, I knew that they were utilised by a variety of animals, from the several primate species found here to bats, bees, squirrels and many bird species. There were also many saplings of the iconic Baobab, personally one of my favourites. It was sad to learn that these beautiful and culturally critical species were being removed at a rapid rate in the area, often illegally and with no respect or care for their importance. As we walk along, Norbert shows me each stage of development, and it quickly comes evident that each species needed special and unique care. While some were potted, others were planted in ‘flower’ beds, others in mini greenhouses. Some needed regular monitoring and feeding, others run the risk of being washed away so needed protection. My admiration for the project kept growing throughout my tour. It was no simple job raising so many species, and their success was a true symbol of the love and care they receive, as the saying goes, you reap what you sow.

Next, we moved away from the nursery and into Norbert’s mini reforestation project, I was amazed how he could pinpoint recently planted trees and knew the ages of most, from a few weeks old to several years. One comment I have often heard from reluctant indigenous planters was that indigenous trees were slow growers, and so it was convenient to just pick an exotic species instead. As we walked through the small forest, a mix of exotics and indigenous, it became apparent that this was not true. Sure, there were many species that were slow-growing but there were also many that were quickly outgrowing their exotic neighbours in a very short span of time. Nobert explained how many of the indigenous species needed a lot of care initially simply because we had changed the landscape so much, many of the species needed shade and protection at the beginning, which they would have got when there was a forest canopy, which is sadly on the decline. Once established, indigenous is incredibly low maintenance and can ‘handle’ themselves, which makes complete sense, this is their home and what they know, if they were going to thrive anywhere it would be here!

After my tour, we head to a local restaurant for lunch and talk about potential partnerships and how Valor to Virtue could best support the nursery’s amazing work. We talk about the need for conversion of private land into forest, the need for protection and more, which I will cover in future blogs, but what I want to focus on here is this age-old practice of planting exotics.

It was evident from my tour that there is plenty of variety that could accommodate any type of outdoor space and that there was a lot of misinformation out there. But I needed to know more to have a fighting chance of changing people’s minds. We talk about the common exotics, like the neem tree, also known as “Muarubaini” meaning the tree of the forty cures. Originally from India, the tree had very much integrated into the landscape and was used by many, but is incredibly invasive and will easily outcompete native species. I often remove neem saplings when I see them, stopping mid-walk to pull them up and throw them away, hoping that I am helping in my own little way. Next, we talk about the endless water guzzling palms that dominate gardens, hotels and beach edges. Purely planted because of the ‘image’ people have of palm-fringed beaches and exotic holidays but have no business to be there. Norbert explains that some species are not as bad as others but in an ideal world should not have ever been here in the first place. Unfortunately, I can’t see this changing soon, just driving down the Diani beach road I see rows of palm trees at roadside tree sellers ‘shops’ and people buying many of them, even speaking with these tree sellers, they will tell you that you can’t do business here if you do not a few palms in your collection, people will ask for them and won’t even consider the indigenous options! We talk of Jacaranda, incredibly popular here, but to any conservationist, is a big no-no. Jacaranda is not necessarily invasive, but it does not add any value to the environment. Like most of these exotic species, they create a green desert, they may look pretty to the eye but wildlife is void. Furthermore, exotics have the potential to change the soil composition, making it more favourable for their counterparts but more difficult for the indigenous. It is very simple, all these plants did not evolve to live here, given that the Kenyan coast is highly endemic and unique, the insects, reptiles, mammals and birds have evolved to co-exist with the native plants. Of course, we cannot expect everyone to create a fully-fledged forest in their back gardens, but couldn’t we just go native instead, or at least ensure there is a healthier ratio?

Why we need to change out planting ways

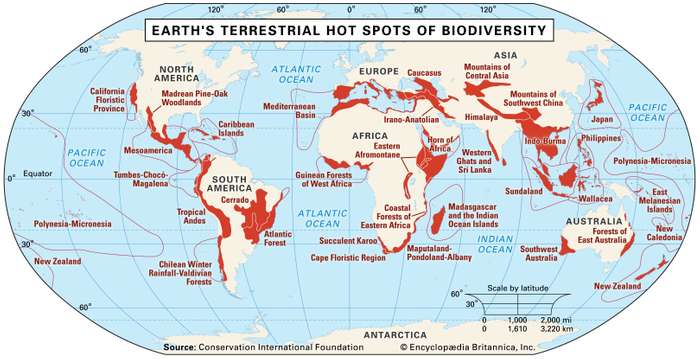

A lot of this has to do with education and the lack of awareness around the topic. Planting is just seen as good, no one ever makes you feel bad for making your garden green, and no one should, but we do need to be mindful of our environment, especially if you are lucky enough to live along the Kenyan coastline, one of the top 25 biodiversity hotspots in the world, known for its endemic plants, birds, butterflies and mammals, that once gone will be gone forever. People will always tell me how lucky they are to live here and to live next to such beauty and wildlife, but if we are not careful we run the risk of making irreversible damage to our landscape, in turn, hurting the wildlife we claim to love. Plants and animals need each other to survive, and we need to respect this. Ultimately we need to change our behaviour and mind frame.